【Meiji Lithograph NFT Art Collection】

Japanese Lithographs

Meiji Period

This collection, “Japanese Lithographs Meiji Period,” is a digital transformation of the “Meiji Lithographs (released in June 1973),” held by the publishing house “Shunyodo Shoten,” which produced numerous works of Meiji intellectuals such as Edogawa Rampo and Taneda Santoka, among others, into NFT art.

As part of Shunyodo (the company’s name at the time) 100th-anniversary commemorative publication, this art compilation was meticulously curated, and limited to 500 copies, each replicated through hand-painted facsimiles from the original first editions.

We hope you will cherish this collection for its significance as a resource for studying Meiji-era cultural artifacts and as a source of artistic appreciation.

- Japanese lithographs are ephemeral life

- Between photography and ukiyo-e

- Unknown art

■Purchase Benefits

・You can use the content image linked to the NFT as your SNS icon.

・We’ll send digital leaflet

The section on Bijin-ga (Pictures of Beautiful Women): 10 pieces

Ukiyo-e flourished over 200 years, and Meiji-era woodblock prints reflects over a span of just over a decade, from the 10s to the 20s of Meiji-era. While the portrayal of beautiful women in ukiyo-e underwent significant changes from Hishikawa Moronobu (????~1694) to Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839~1892) and Mizuno Toshikata (1866~1908), the depiction of beautiful women in Meiji woodblock prints is confined to the early and mid-Meiji period. In other words, it is a reflection of the beauty ideals of the Meiji era. As the age of modernization and enlightenment unfolded, the so-called “Rokumeikan era” continued for a while. It was as if by chance, during the heyday of woodblock prints, eminent ladies, their long skirts trailing, indulged in dances. However, common people eschewed audacity, and the feudal tradition of valuing a modest way of life persisted. Therefore, the beautiful women depicted in woodblock prints do not boast grandeur in their appearance but rather aspire to conceal their charm in an elegant manner.

Furthermore, when it comes to Meiji-era beauties, tradition dictated that the appearance of geisha took precedence. Following them were high-status, reputable gentlemen’s daughters. Rarely would there be appearances of teahouse starlets like those in nishiki-e prints or, as in the modern day, singers and dancers from the streets (excluding popular prints).

While there are resemblances in poses between photographs and woodblock prints, they have influenced each other in various ways. When a particular pose of a beautiful woman gains popularity, other publishing houses quickly release similar poses. Often, the only difference is a slight change in costume patterns. Also, when Western-dressed or Japanese-dressed pairs of beautiful women become fashionable, companies keep launching similar compositions with variations in background or a swap in the positions of the women. This phenomenon existed in nishiki-e prints from the past, but it seems to have been driven by commercialism.

1.Tokyo Geisha Woman

1878(Meiji 12, Gengendo, Illustrated by Masaji Hiraki

“This is the oldest beauty portrayed in woodblock prints that I have ever seen,” says Yoshida Kogoro. In the previously mentioned ‘In Hiraki Masaji’s Recollections,’ there is a passage that goes something like, “From the second woodblock print onwards, I decided to paint a half-length portrait of a famous geisha in Tokyo and so on.” The description is accurate, and the color work is skillful, most likely the handiwork of Hiraki himself. Unlike works from the following two decades, this one is meticulous and solid. In Meiji 6, Hiraki came all the way from Kokukouryou in Bitchu Province to Yokohama, entered the school of Goseda Houryu, trained in Western-style painting, and later became associated with Gengendo, where he actively produced woodblock prints.

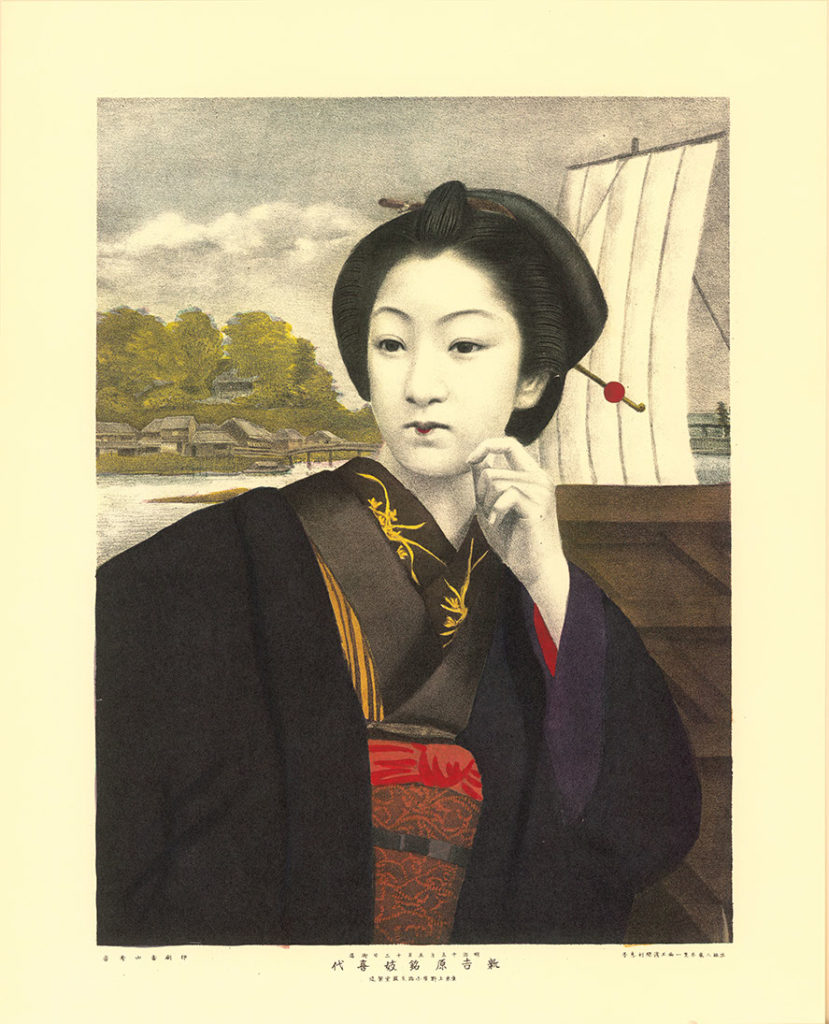

2.Renowned Name Kikiyo in ShinYoshiwara

1881(Meiji 15, Published by Shiichi Kamei, Illustrated by Rieko Asama)

This woodblock print features the beautiful figure of Geisha Kikiyo, who exudes an air of an accomplished elder sister, with a yakatabune (pleasure boat) floating on the Sumida River in the background. It’s worth noting that, at that time, the traditional Japanese hairstyle called “Sokuhatsu” was already popular among geisha. With the exception of Western-style attire, nearly all of them had Japanese hairstyles. The fashion of that era included large, white collars protruding from the kimono, which had black silk crepe collars attached. The black outer kimono, brocade obi sashi, a hint of red undergarments visible from the sleeve cuffs, hair neatly arranged in the Shimada style adorned with coral hairpins—all these elements harmoniously combined in this woodblock print.

3.Renowned Geisha Oyanagi in Tokyo This Spring

1881(Meiji 15, Published by Shiichi Kamei, Illustrated by Rieko Asama)

Depicting the geisha of this spring, the background features Shinbashi Station with a railway carriage and rickshaws. The youthful and innocent Geisha Oyuri, accompanied by her elder companion, stands out. Her kimono is likely made of fine crepe silk, an unpatterned, plain oriole color, which adds an element of elegance. The mood in the distant sky, with drifting clouds, is something that cannot be replicated in nishiki-e (brocade pictures). This is a heartwarming scene, a quintessential feature of Meiji woodblock prints.

4.Renowned Geiko Koji in Shitaya, Tokyo

1882(Meiji 16, Illustrated and Published by Shiichi Kamei)

The author, Shiichi Kamei, was originally from Edo. He was born in 1843 (Tenpo 14) in Dohocho, Shitaya, and studied Western-style painting under Matsusaburo Yokoyama. He was known for wielding a brush in the pages of the Hochi Newspaper and creating many woodblock prints at Gengendo (he also seems to have managed a woodblock printing business while supporting his family). In “Biographical Sketches of Western-Style Artists” (Meiji 41, written by Nishikiyoshiro Honda), it’s mentioned, “You always create portraits according to people’s needs, satisfying them with your beauty. Your specialty is undoubtedly in the portrayal of beautiful women.” This piece, set against the background of Toshogu Shrine on the shores of Ueno’s Shinobazu Pond, truly demonstrates his skill in capturing the subject’s pose. The texture in the image is also finely detailed.

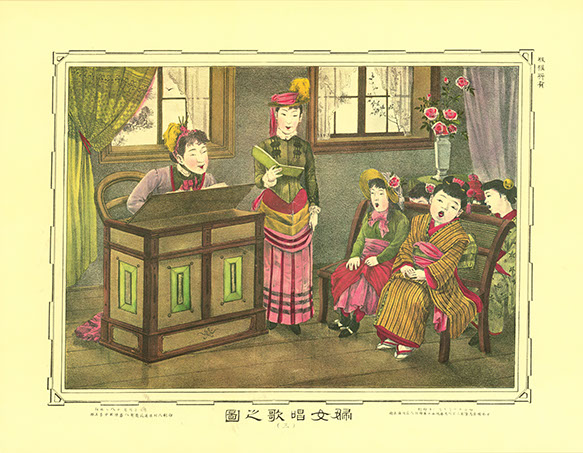

5.Image of Women Singing

1887(Meiji 21, Illustrated and Published by Fujihyoue Arakawa)

It is said that Western music in Japan began with military bands and hymns of associations. In 1872 (Meiji 5), students were introduced to music, and “singing songs” were included in elementary school subjects, while “playing music” was part of middle school, though it was noted that “for the time being, this would be lacking.” Perhaps there was no adequate preparation at the time. In 1879 (Meiji 12), the Ministry of Education established a Music Inspection Bureau, largely motivated by recommendations made to the then Minister of Education, Kanetaro Mekata and Shuji Izawa, who were both in the United States. The Music Inspection Bureau was renamed the Music Inspection Office in 1885 (Meiji 18), and further evolved into the Tokyo Music School in 1887 (Meiji 20).

The first schools in Japan to actively teach music were the Tokyo Teacher’s Schools for boys and girls, and this image pertains to the attached elementary school of Ochanomizu Women’s Normal School. It portrays a heartwarming scene. By the way, organs were already being produced in Japan in 1881 (Meiji 14).

6.Ochiyo in Yanagibashi Bridge

1887(Meiji 21, Illustrated by Genjiro Fukumiya)

The beautiful lady standing by the former Yanagibashi Bridge holds a parasol with a distinctive snake skin’s pattern. Her expression is exceptionally serene and composed. Her kimono features a crepe collar, possibly Hachibunjo, and reveals a collar with a ginkgo leaf motif. She is adorned with the same characteristic boxwood comb and coral hairpin, which were typical fashion items of the time.

In the background, a swallow flits about in the silver-threaded rain. Unlike nishiki-e woodblock prints, which are drawn with lines, this depiction captures the likeness of the subject as if it were a real photograph, which is a unique characteristic of woodblock prints. This particular artwork stands out for its particularly harmonious use of colors.

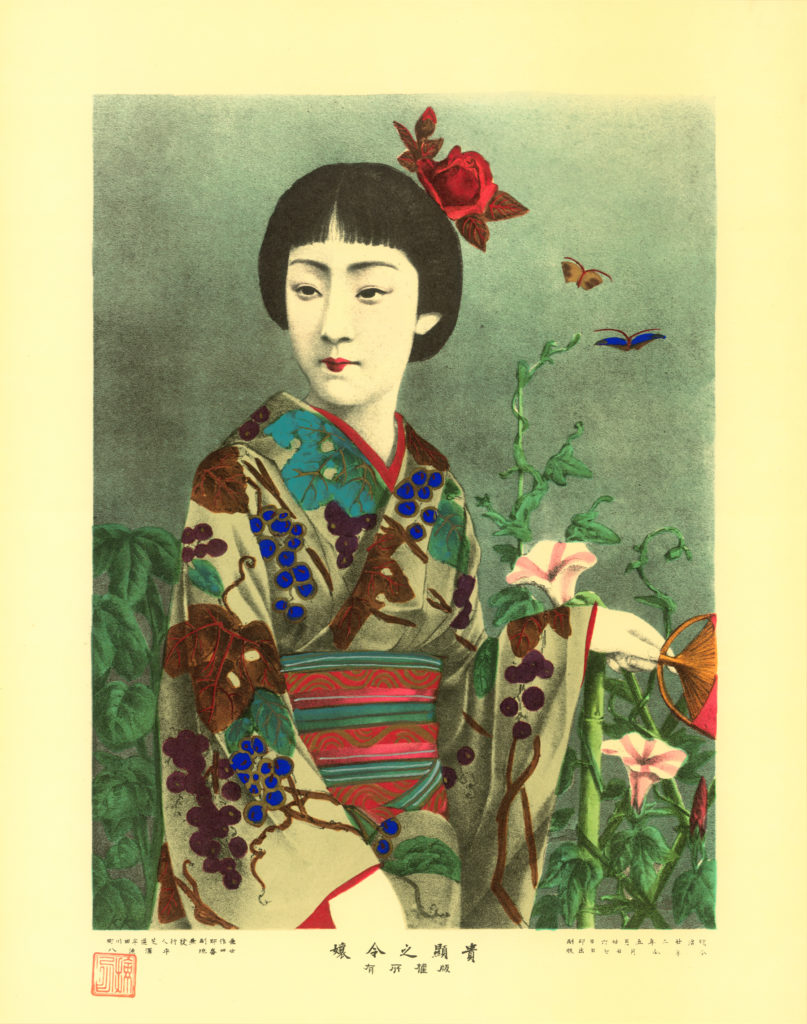

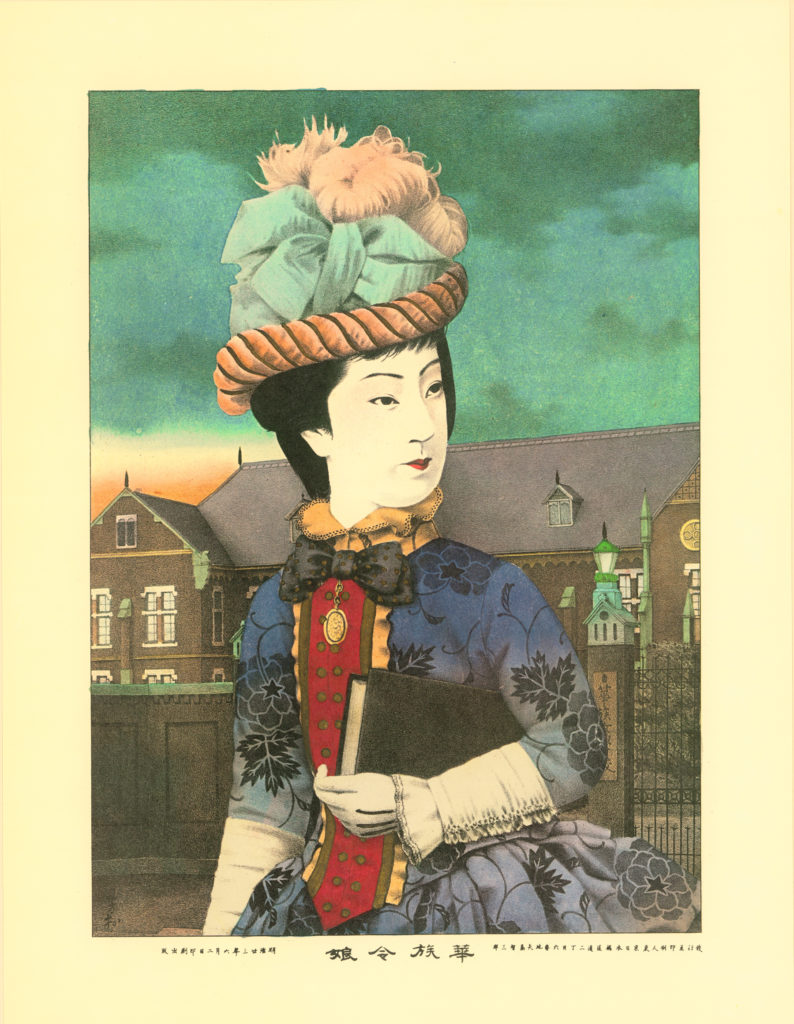

7.Eminent Lady of Distinction

1888(Meiji 22, Illustrated and Published by Sonji Nakai)

The young lady from 1888, quite astonishing, isn’t she? Even if you were to let her stroll through today’s Ginza, she wouldn’t look out of place. At the time, her kimono’s design was remarkably bold, but her appearance carries an air of sophistication. It was a feature of the high-society fashion of that Meiji era to adorn hairpieces with roses, and nearly everyone wore rose flowers. It seems this particular illustration gained significant popularity, as there are quite a few woodblock prints featuring high-society beauties in the same pose. This one, however, represents a select choice among them.

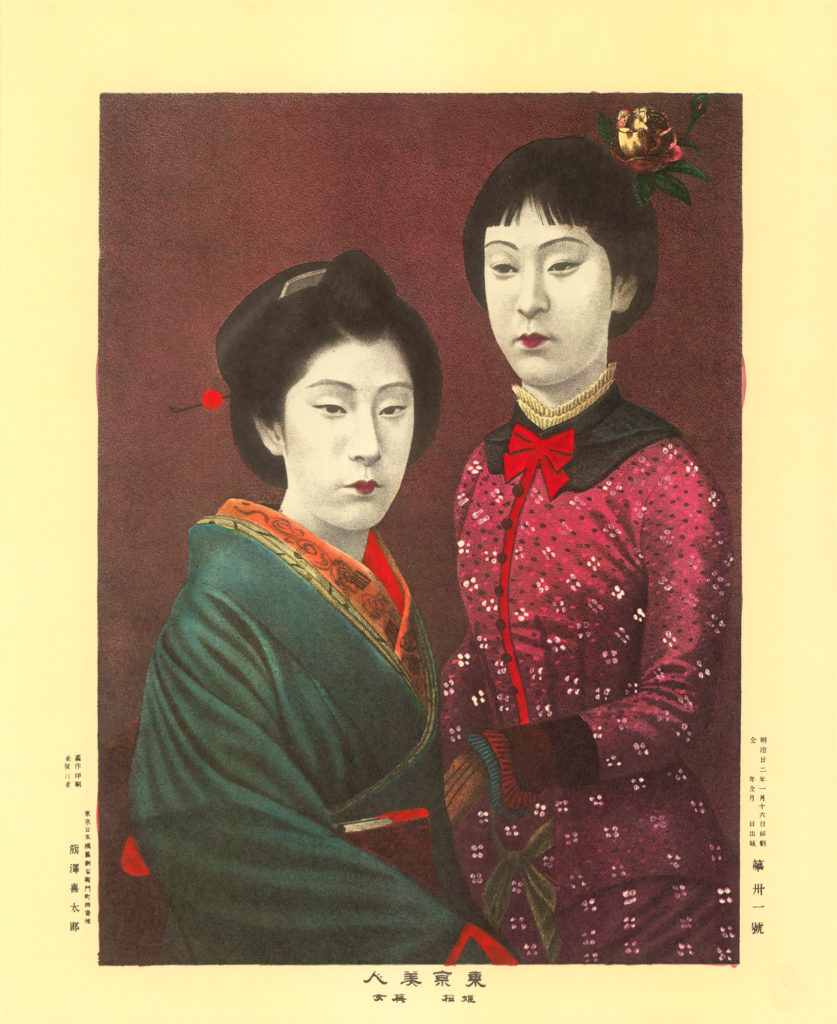

8. Image of Women Singing Hymns

1888(Meiji 22, Illustrated and Published by Kitaro Kumazawa)

On the right, there’s a lady in Western attire, and on the left, one in traditional Japanese attire, and both are geisha. During the flourishing days of the Rokumeikan, it was not uncommon to see geisha in Western clothing. Additionally, the practice of “Sokuhatsu” hairstyles was considered both economical and hygienic, contributing to its popularity. The juxtaposition of these two lovely women is rather appealing. The pairing of beauties in Western and Japanese attire seems to have appealed to the spirit of the times, leading to the publication of similar woodblock prints from various printing houses. This particular piece, with its pose and coloration, has a certain charm, and can be deemed a fine work.

9.Image of Women Singing Hymns

1889(Meiji 23, Published and Printed by Tomosaburo Yajima)

A high-spirited, high-society young lady. She is seen leaving the gate of an aristocratic girls’ school. Perhaps she is rushing to attend a dance lesson, a trend of that time. I’ve seen the same illustration with entirely different color schemes, but this one appears to be better. In Meiji woodblock prints, even with the same image, there’s room for choice. Although it’s signed “Yoshimura,” the family name is unclear.

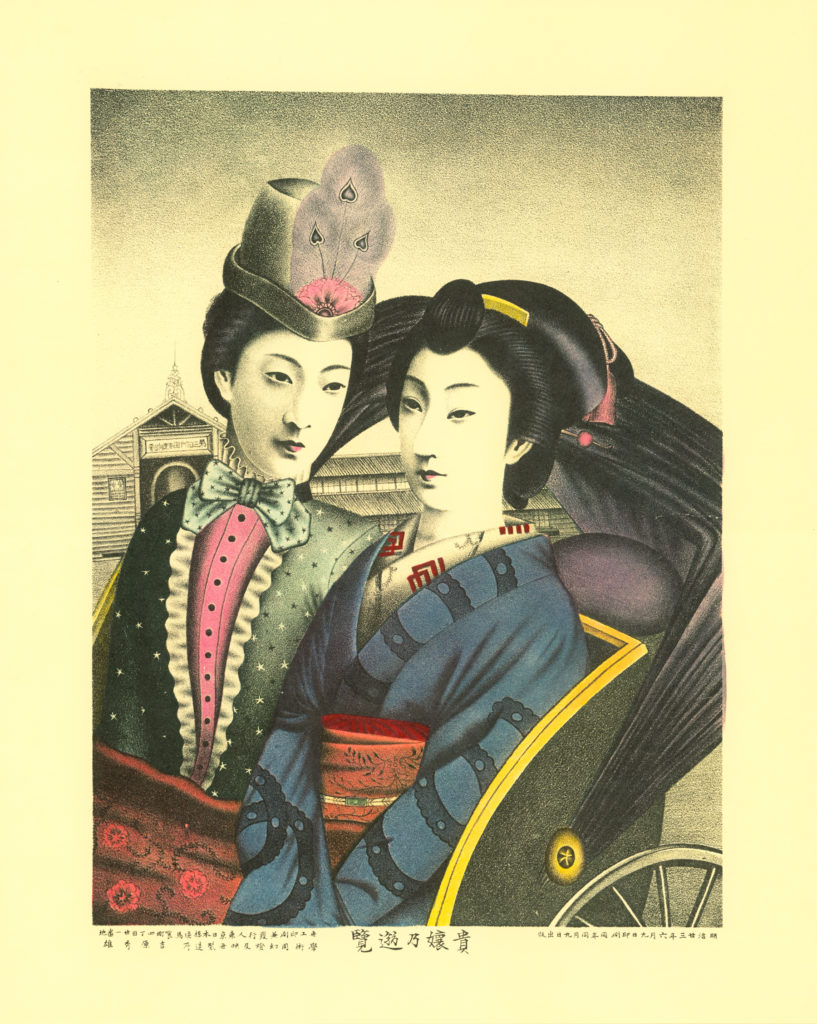

10.Image of Women Singing Hymns

1889(Meiji 23, Illustrated and Published by Hideo Yoshihara)

Both women riding in the rickshaw are of high status and are daughters of well-known gentlemen. Whether in Western or traditional Japanese attire, both of them exude sophistication. This may have been on their way back from the Third National Industrial Exhibition held in Ueno this year. The composition is well done, although there are slight irregularities in the rickshaw. This was created in 1889 (Meiji 23), and just two years later, beautiful woodblock prints like this would become a rarity.

The section on Landscape Prints: 10 Pieces

As the late Edo period arrived, the publication of landscape prints, known as “Nishiki-e,” flourished. People, despite their own surroundings, always longed for the landscapes of other regions. This sentiment remains constant across eras. When Edo transformed into Tokyo and assumed the enlightenment of modernization, lots of Nishiki-e prints appeared ,featuring various depictions of Tokyo, from small size to large size.

Then woodblock printing came, introducing realism, photographic precision, and lifelike landscapes. In a sense, this surpassed the aspirations of Nishiki-e artists. Where Nishiki-e artists would represent a sphere with a simple circle, woodblock artists would create the illusion of a sphere through the intricacies of grainy shading. The marvel and novelty of this technique naturally captivated people’s hearts.

Woodblock landscape prints have already been published around 1877 (Meiji 10). The predecessor of the Printing Bureau, known as the Paper Money Bureau, produced quite sophisticated pieces. Kiyosone and his disciples, Yuichi Takahashi in Gengendo were well known on these prints. General woodblock prints featuring landscapes began to appear across Japan, and later, they extensively depicted Tokyo landmarks around Meiji 15-16years.

Even though Nishiki-e prints also embraced the influences of modernization, portraying the brick streets of Ginza, steam locomotives, and horse-drawn carriages, woodblock artists couldn’t ignore these subjects. When the prints captured their subjects with photographic precision, the public eagerly embraced them. Woodblock prints of Tokyo landscapes were published with enthusiasm and became popular souvenirs, spreading to various regions in astonishing quantities. Among them are numerous beloved works.

11.Picture of a Distant view of Yasukuni Shrine on Kudan Slope, Tokyo

Date Unknown ( Published by Shougyousha, Original Publisher Denjirou Genhashi)

Yasukuni Shrine was founded in 1869 (Meiji 2) and is also known as the “Shokon,inviting soul, Shrine.” In the “Tokyo Meisho Zukai” published in 1877 (Meiji 10), it is described as follows: “This place is on the highest hill where you can overlook the entire city at a glance. There is a stone lantern on the right side of the slope, built with natural stone, and it is several feet high. It serve as a landmark at night to guide those who are lost in the darkness.” This illustration is considered the masterpiece of Meiji-era stone lithograph pictures, both in composition and color by Kogoro Yoshida. The author and the exact date are unknown, but it was likely created around the 12th to 13th year of Meiji, and the author was probably a skilled artist. Even after carefully examining over a thousand stone lithographs, no other versions have been found.

12.Scenic View of the Morning Cherry Blossoms on Sumida Embankment

1883 (April, Meiji 16)

During the Meiji era, it was often mentioned that schoolchildren wrote compositions about “bringing a gourd and playing on Sumida Embankment.” Sumida Embankment, also known as Sumida River Embankment, was one of the suburban cherry blossom viewing spots along with Koganei, and it was a popular leisure destination at that time. Therefore, many stone lithograph pictures of Sumida Embankment can be found, with a majority depicting people under cherry blossoms in various states of merry revelry.

However, this picture shows Sumida Embankment in the fresh morning light, surrounded by cherry blossoms. It was produced in Meiji 16, making it an old and rare landscape in the world of framed pictures. This area is often associated with what’s called “Hyappon Kui” (A Hundred Piles), and Kiyochika also depicted the vicinity of Hyappon Kui at dusk. Nevertheless, this image captures a refreshing and pure morning landscape.

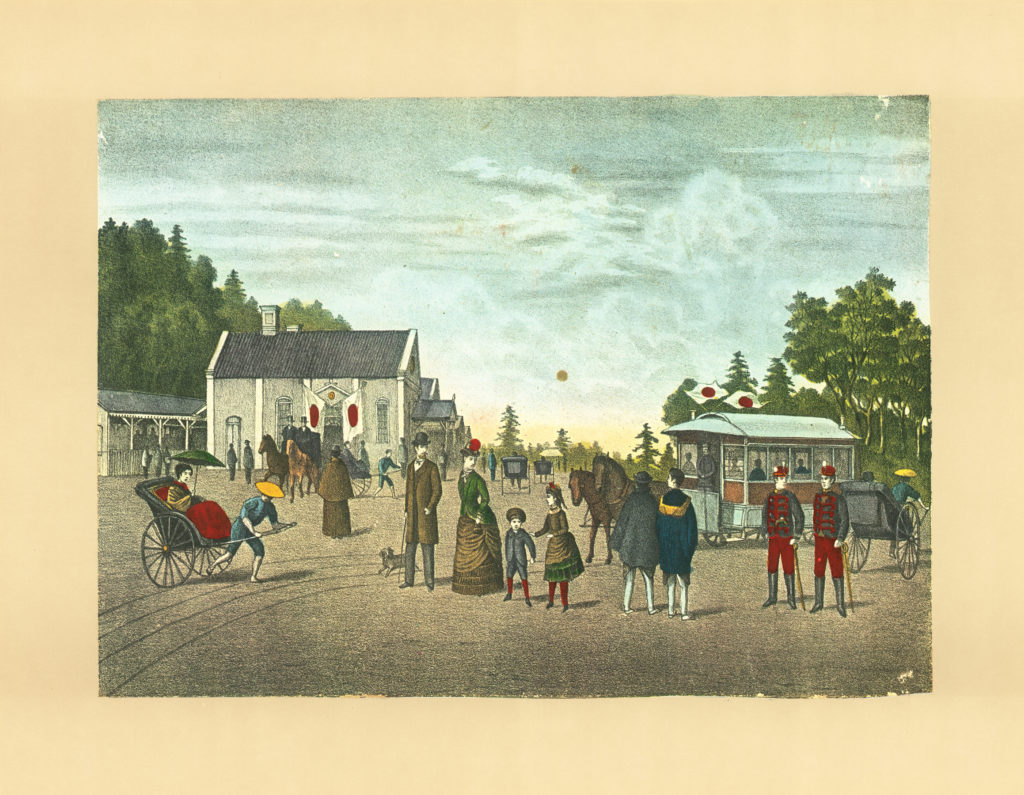

13.Picture of Ueno Station

Date Unknown

Regrettably, this picture lacks the margins around the image, making the title and the exact date unclear. However, it is highly likely that this depicts Ueno Station during the opening ceremony of the Japan Railway Company, which opened the Ueno-Kumagaya route in 1883 (Meiji 16) and the Ueno-Takasaki route the following year in 1884. The technique, colors, and grain structure strongly suggest that this picture is indeed from Meiji 16. It may have been a means of depicting Westerners in their foreign attire. While a train carriage is stopped, it should be noted that the railway opened in the previous year, Meiji 15. The red-ribbed military attire, travelers, the back of a gentleman in an Inverness cape, a two-horse carriage, and rickshaws—all the tools of the Meiji era are present. Even for those who are not familiar with the time, it can be nostalgically appreciated.

14.Scenic View of Asakusa Kannon Temple in Tokyo

1885 (August Meiji 18, Published by Shiichi Kamei, Illustrated by Fukumiya Genjiro)

While woodblock prints often depicted Asakusa Temple, stone lithograph pictures featuring it are not uncommon either. There are views from the front, from the side, and even from behind Benten Pond. This one, of course, shows Asakusa Temple from the east side. In Meiji 18, Asakusa had yet to see opera or motion pictures, but within the temple grounds, one could find “UeRoku,” a flower garden operated by Uekiya Rokuzaburo, as well as an archery shop, a quick photography studio, panoramas, and entertainers performing the tricks of Matsui Gensui’s spinning tops. On the left side, you can already see Western-style benches under a large tree. Most of the visitors are dressed in traditional Japanese clothing, but there’s a gentleman wearing a top hat and holding a cane or a Western-style umbrella. The Niomon Gate, the five-story pagoda, and the main hall might be perceived as overpriced at first glance, However, within this scene lies a distinctive feature of the golden age of stone lithographs.

15.True Scene of Azuma Bridge

December 1887 (Meiji 20, Illustrated and published by Roku Yajima)

Azuma Bridge, which was described as ‘magnificent and truly a symbol of the suburbs of the capital’ at the time, was completed in December of Meiji 20. Therefore, this picture was likely released almost concurrently with its completion. It’s evident that the lithographer worked hastily to capture this significant achievement. Azuma Bridge quickly became a popular subject for both woodblock and stone lithograph artists. There are various depictions of Azuma Bridge from different angles within the realm of lithography, with scenes like pleasure boats cruising beneath the bridge and evening views with food stalls at the bridge’s edge. The Western art perspective technique was skillfully applied, creating a photographic quality that surely led to high demand for this artwork and made it a coveted souvenir for those from the countryside.

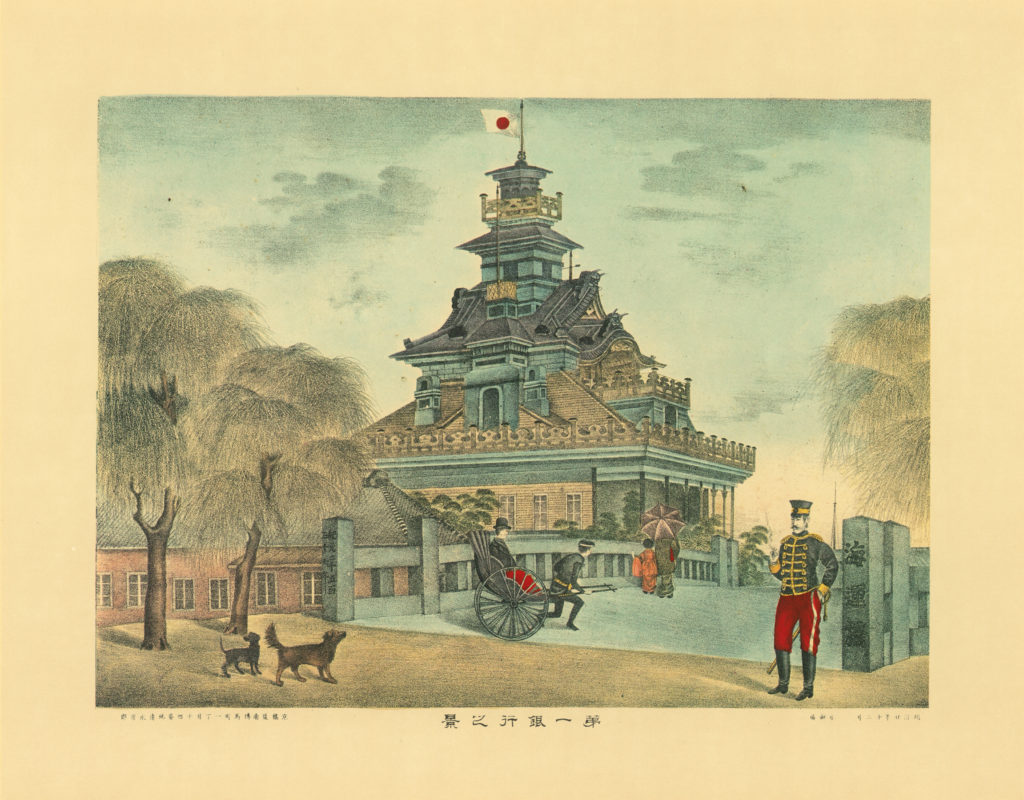

16.Scene of the First National Bank

1887(Meiji 20, by Ichiro Shimizu)

In 1873 (Meiji 6), the National Bank Act was established, and in Meiji 10, the First National Bank was founded. In the district of Kabuto-cho near Nihonbashi in Tokyo, it was an unusual sight with a five-story Western-style building near the Kaiun Bridge. In the book ‘Tokyo Meisho Kan’ (written by Kyu Aizawa in Meiji 25), it is described as, ‘Located in Kabuto-cho near Kaiun Bridge… It became the National Company around the Keio era, and after the Meiji Restoration, it was a silk reeling factory and eventually became the First Bank. It was a five-story brick building with a high roof, and the architect was the famous Kisuke Shimizu, who was in charge of our national bank. Eiichi Shibusawa served as the president.’ The Tsukiji Hotel, which burned down in the Meiji 5 fire, was also designed by Kisuke Shimizu. It somewhat resembles a stylish castle. It was common in the scenic pictures of that era to depict military officers in uniforms with lapels. Similar to the West, military service was a somewhat aspirational profession at the time. This adds a nice touch to the overall image.”

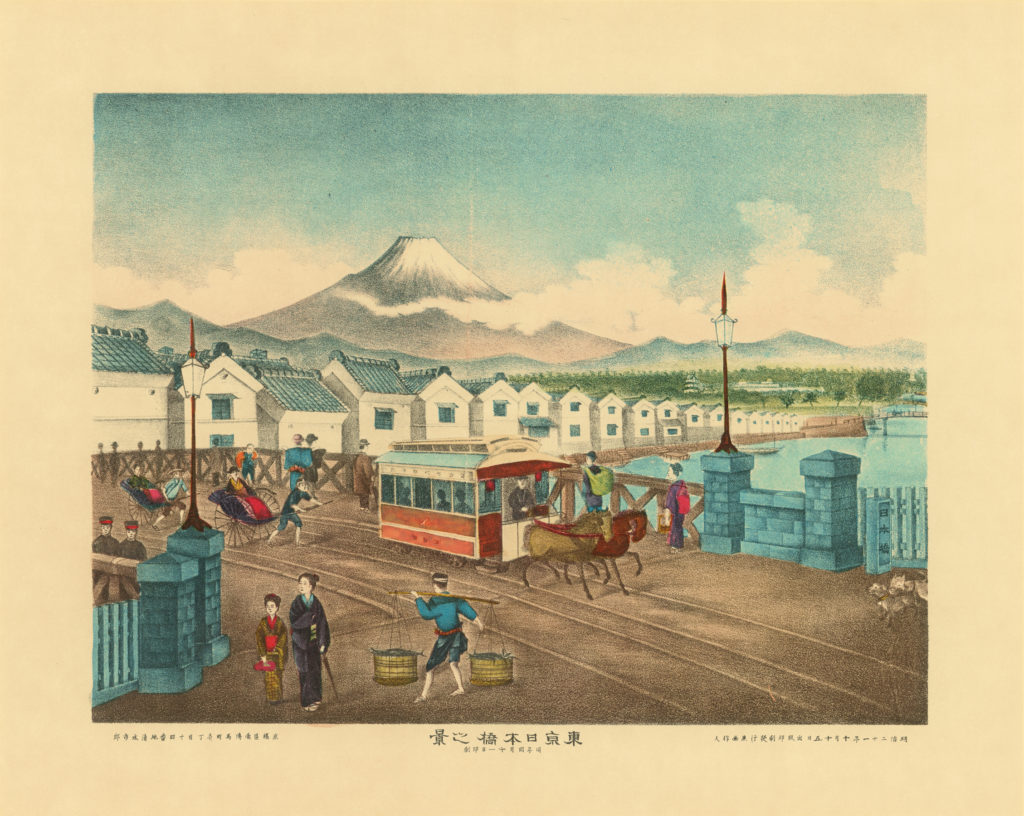

17.Scenery of Tokyo Nihonbashi

1888 (Meiji 21, published and printed by Ichiro Shimizu)

While the first Nihonbashi bridge was built in the year 1603 (Keicho 8), it became the reference point for the national highway system in the following year. It’s not clear how many times it was reconstructed afterward. In 1885 (Meiji 18), a large fire occurred at Nihonbashi, so the bridge in this picture was likely reconstructed after that incident. Originally, it should have had “giboshi” on the railings, but in this picture, the bridge is stone-built and features gas lamps. In Odawara-cho near here, there is a fish market, and people carrying scales are seen, so this should be the morning scene. According to the people of that time, it was described so busy , but dogs are also seen playing, and everything seems rather leisurely. More importantly, there are white-walled warehouses along the riverside, and it was a time when there were no tall buildings or smog. As a result, Chiyoda Castle and even Mount Fuji are clearly visible. It was not a mere figment of the imagination.

18.Illustration of the Taikobashi Bridge at Kameido Tenjin Shrine

1888 (Meiji 21, Illustrated and published by Yoshiro Yabusaki)

he Taikobashi Bridge in Kameido is also featured in Hiroshige’s “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.” It is often written as “亀戸” and pronounced as “Kameido” due to the pond in front of the Tenjin Shrine, which serves as a substitute of “ i “. Nevertheless, this picture is truly delightful. It captures the subtlety of composition. On the red-carpeted seating of the tea house, there is a smoking set, along with a gentleman wearing a tall hat at the top of the Taikobashi Bridge, a lady and her daughter at the edge of the near bridge – the coloring and details exude a certain charm. Particularly, the untouched whiteness of the wisteria adds an enduring flavor. Though the work of an unknown artist, one might want to consider this as a masterpiece.

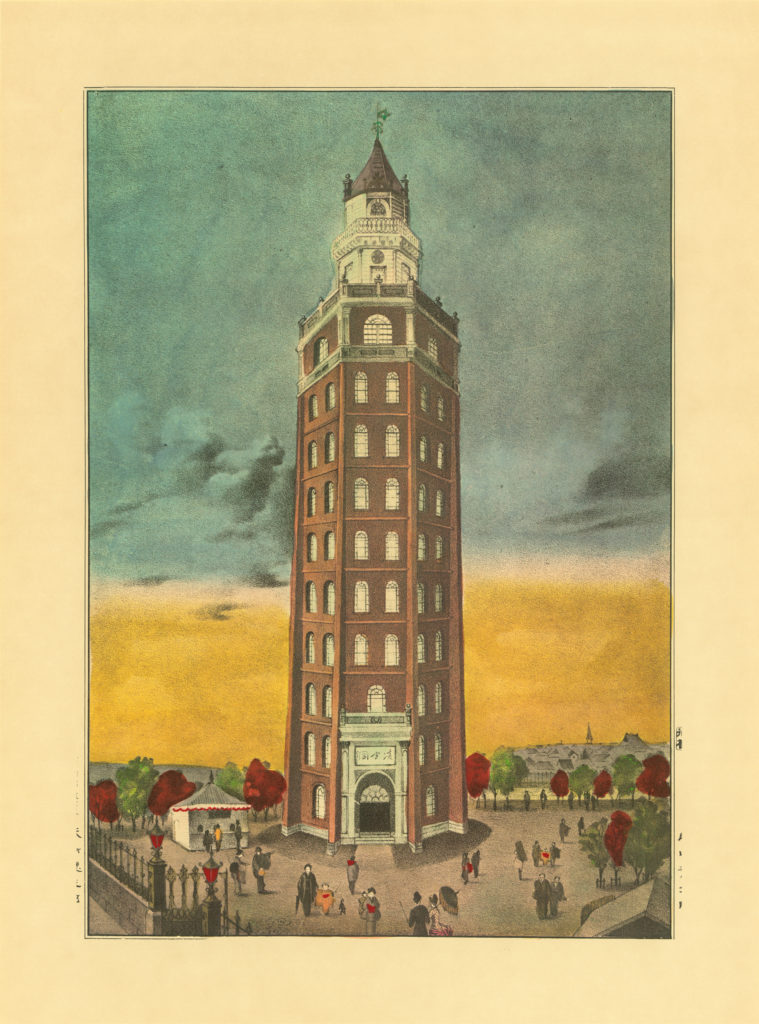

19.Asakusa Ryouunkaku Tower Image

1890 (Meiji 23, designed by Shigetaro Katsuyama)

In November of 1890 (Meiji 23), a remarkable structure, referred to by Kubota Mantaro as “a startling twelve-story building,” was erected behind Okuyama park of Asakusa. It was designed by the Englishman named Bandon and was constructed entirely of brick, standing at a height of 36 kan (approximately 65 meters). At the time, it was considered an exceptional building. It was named “Ryouunkaku,” also known as “Twelve Stories.”

Initially, the tower had an elevator, but it was soon discontinued. Instead, it had a spiral staircase in the center, allowing visitors to ascend one step at a time. Inside, there were shops, exhibits, theaters, dance halls, and more. On the tenth floor, there was a teahouse for resting, equipped with telescopes. The exact origin of this image and the publisher are uncertain, but it is undoubtedly the work of Shigetaro Katsuyama, as depicted in “Asakusa Ryounkaku No Zu” in the year Meiji 23. Similar images of this kind were also released by various publishers in the same year.

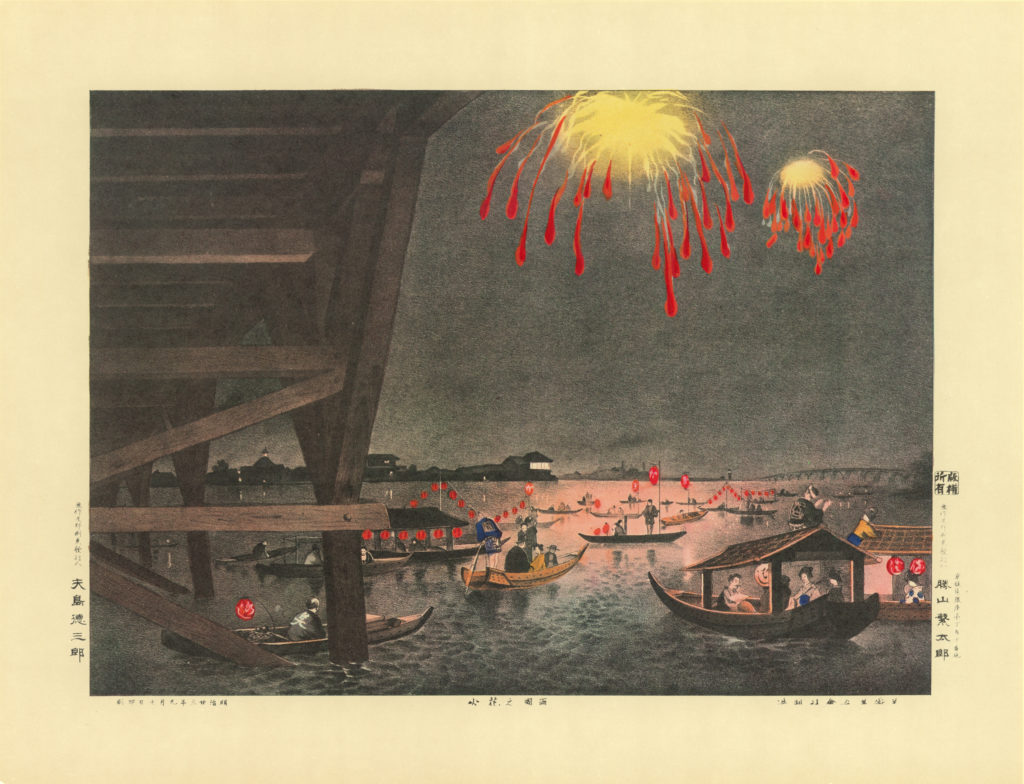

20.Both Countries’ Fireworks

1890 (Meiji 23, created, printed, and published by Shigetaro Katsuyama)

Within Hiroshige’s “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo,” there is an image called “Ryogoku Bridge Fireworks.” It is a particularly desolate scene. The tradition of river openings reportedly began in 1733 (during the 18th year of the Kyoho era). However, in 1962 (the 37th year of the Showa era), due to concerns about the risk of fire, it was regrettably canceled.

In Keigoro Okabe’s “Tokyo Meisho Kokkai” (the 10th year of the Meiji era), it is described, “Annually, on the 28th of May (according to the new calendar, equivalent to early July), fireworks are set off in celebration of the river opening. On this evening, both shores are filled with teahouses and restaurants, while numerous boats on the river are adorned with tens of thousands of lanterns. The merriment continues until late at night. On the bridges and riverbanks, tens of thousands of spectators gather, that scene is very grand.” The exaggeration in the text is also quite fascinating.

This image, taken from an unnamed artist, is inspired by Kiyochika’s “Ryogoku Hanabi no Zu” (Fireworks at Ryogoku), and it captures the essence of the event.

©SHUNYODOSHOTEN, All Rights Reserved.